From Flanders with Love

WWI saw the mass mobilisation of men from all parts of the UK to serve on the Western front and for many it was the first time they had ever been away from home. It soon became apparent that not only was the conflict not “going to be over before Christmas”, but also that the hardship, suffering, death and injury on the front line were all too real. Reassuring those at home that you were well, and knowing that you had someone at home thinking about you, became crucial for keeping up morale.

Letters and parcels were an extremely important part of this. The Imperial War Museum’s ‘Letters To Loved Ones In The First World War’ reported that during the course of the war, the British Army Postal Service delivered around 2 billion letters and in 1917 alone, over 19,000 mailbags crossed the English Channel each day. But all mail was censored to ensure that any information that might be useful to the enemy, or undermine morale and cause unrest at home, was not reported.

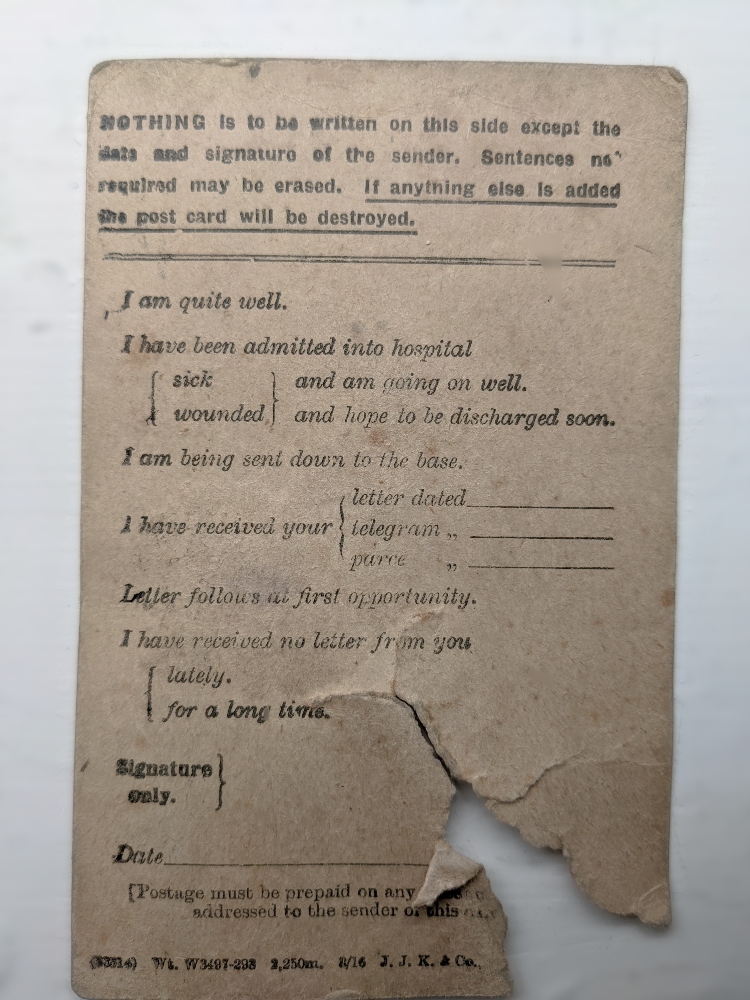

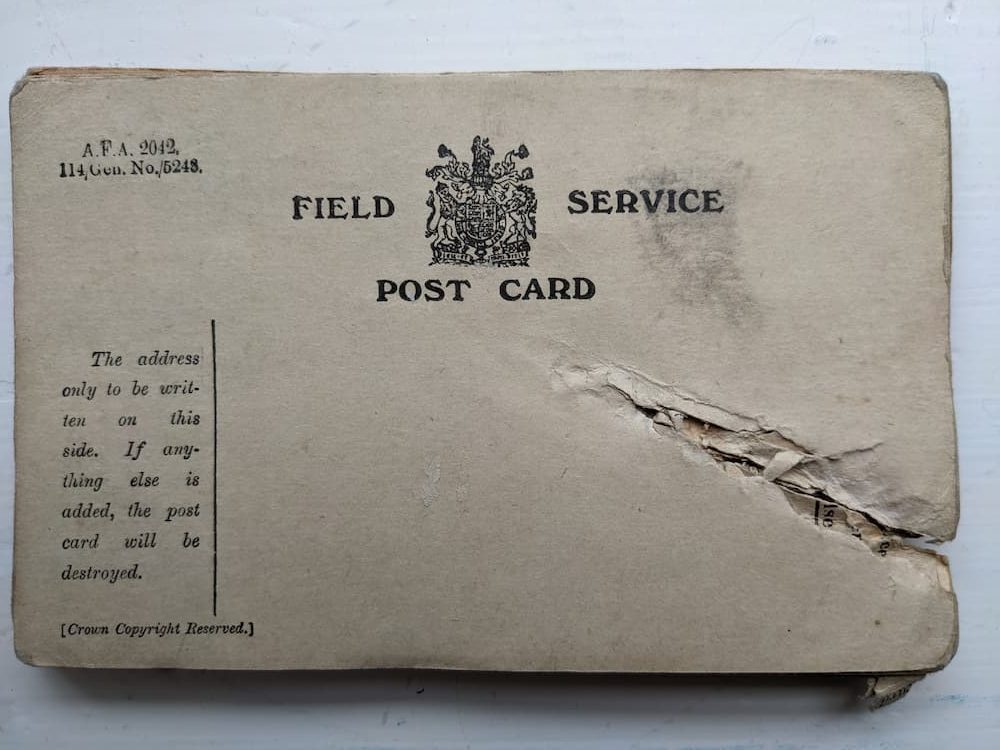

Letters also required paper and a dry and quiet place to write, something not readily available in the mud and grime of the trenches. One solution was the Field Service Postcard, a pre-printed card with a selection of standard phrases like “I am well” or “I have received your parcel”, which rather like text messages today, introduced a fast and easy way to re-assure loved ones that all was well. This example held in the museum archives shows signs of a bullet passing through the pack, so these particular cards not only kept the holder in touch with life at home but possibly saved his life abroad too.

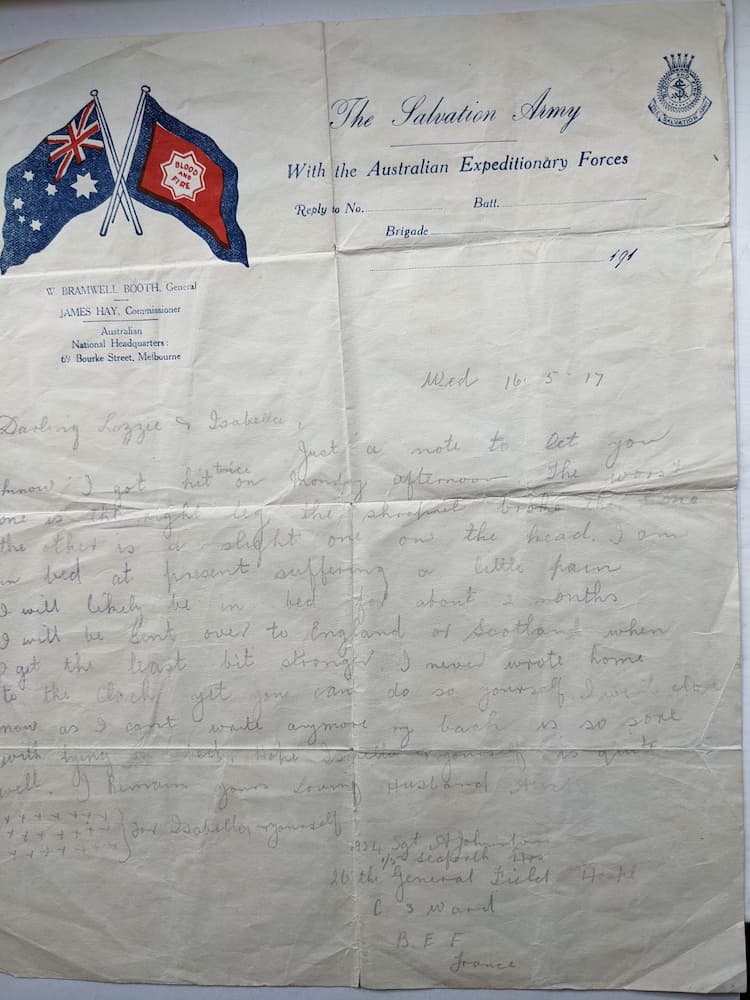

To avoid rejection by the censor, only the date and sender’s name could be added to the card, so more overt expressions of affection required a letter. In this example written from a field hospital by Sergeant Alexander Johnstone to his wife “Darling Lizzie” and daughter Isabelle, he rather sweetly includes a stream of kisses at the end of the letter “for Isabelle and yourself”. Interestingly the note is written on paper supplied by the Salvation Army with the Australian Expeditionary Force, although Sgt Johnstone served with 1/5th (The Sutherland & Caithness Highland) Battalion Territorial Force of the Seaforth Highlanders, so presumably he made use of whatever paper was available.

He describes his wounds but no mention of where or how received – details that would almost certainly have been cut by the censor. The letter is dated Wednesday 16th May 1917 and he states that he “got hit twice on Monday afternoon”, presumably meaning 14th May. If so, then he probably received these wounds when the 1/5th took part in the capture and defence of the town of Roeux, in northern France, as part of the wider Battle of Arras. Following five failed attempts to take Roeux, a sixth assault was launched on 11th May and the 152nd Brigade of the 51st Highland Division, which included the 1/5th Seaforths, joined the action on 13th May after the Germans had withdrawn. Throughout 14th May, a German artillery counter bombardment was laid on to 152nd Brigade’s positions around Roeux and as he mentions shrapnel breaking his leg, this is most likely where Sgt Johnstone came to be wounded.

Fortunately, he survived the war and would have been able to turn those paper kisses in to real ones once he had been repatriated to Scotland. With St Valentine’s day approaching, many of us will be sending our own messages and cards of love and affection, but happily with nothing scarred by a bullet, shrapnel or censor.

By Craig Durham, Volunteer at The Highlanders’ Museum