The Fall of Tobruk

80th Anniversary Special

The 21st June 1942 not only marked the mid-summer solstice but also, as it turned out, the mid-point of WWII and whilst it was the longest day of the year for those at home, it proved to be one of the bleakest days for the 2nd Battalion Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders in Tobruk, Libya.

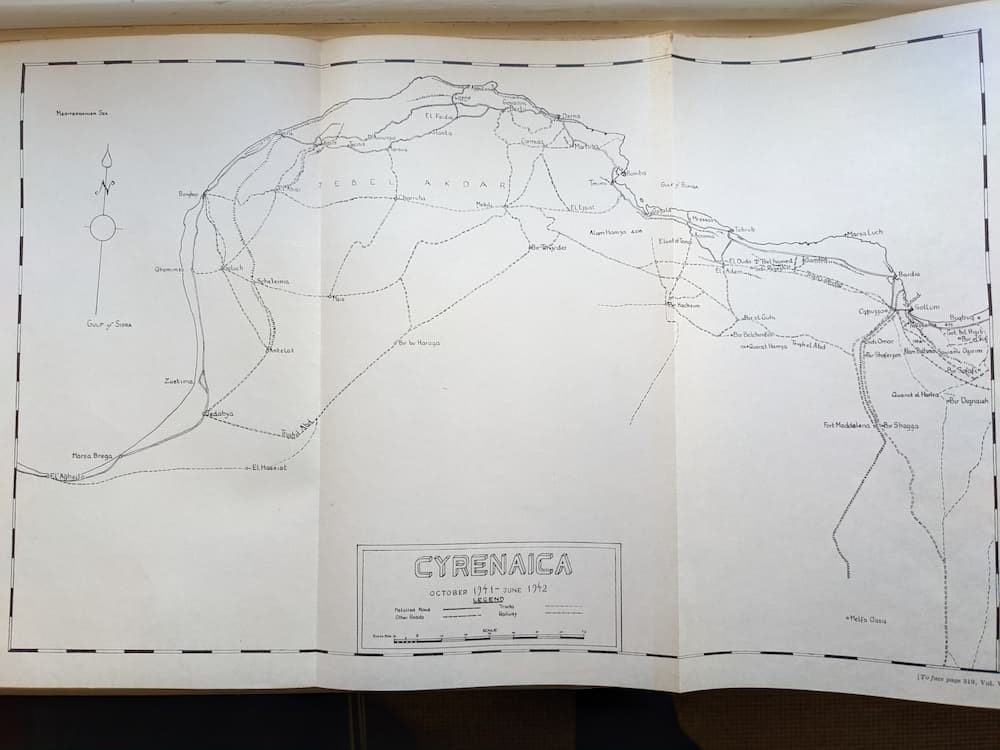

In early 1942 the Axis and Allied armies in North Africa had fought to an uneasy standstill along the Gazala line, an 80km long series of defensive boxes stretching inland from the coast of Libya, approximately 50km west of Tobruk. On 26th May, the Germans attacked in strength, outflanking the Allies to the south and breaking through in several sectors. Over the next three weeks, the Allies were pushed back to Tobruk which was defended by the 2nd South African Infantry Division, under the recently appointed command of Major-General HB Klopper. The 2nd Camerons, as part of the 11th Indian Brigade on detachment from the 4th Indian Division, were tasked with holding a three-mile line on the southern perimeter.

Early on the morning of 20th June the Germans made a concerted assault on the south eastern outer defences. Smashing their way past the 2/5th Mahrattas in the centre and leaving the 2nd Camerons and 2/7th Gurkhas isolated on the right and left respectively, the German panzers were in the centre of Tobruk by early evening. Although the bulk of the 2nd South African Division had not yet engaged with the enemy, General Klopper made the decision to surrender to avoid further bloodshed, and the Division HQ formally surrendered early on the morning of Sunday 21st June. Due to the speed of the German breakthrough and inevitable confusion between Division, Brigade and Battalion HQs, Lt-Colonel Colin Duncan, commanding 2nd Camerons did not receive word of the surrender until 10am, and refused to believe it as they had barely had contact with the enemy at that point. Without specific orders to the contrary, the Camerons fought on until after dark, knocking out several Italian tanks, until a German officer came forward under a white flag to inform them that they were the only battalion still fighting, and to insist on their immediate surrender or face annihilation.

Lt-Colonel Duncan promised a reply by 5am the next morning and the Germans agreed to postpone further attacks if the Camerons would undertake to parade on the El Adem road at that hour ready to march into the prison pens. Lt-Colonel Duncan gave his assurance that he would be there but added that he expected very few of his battalion to be on parade at such an early hour! During the night as much stores and equipment as possible was destroyed before orders were issued relieving the men of their duty and encouraging them to make their escape.

Sergeant Lloyd of the South African army, writing in the magazine Outspan after the war, described what happened next:

“It was mid-day when we heard it. Faintly at first and then louder it came, a rhythmic swinging sound, unexpected but unmistakable – the skirl of pipes. We scrambled out of our shelters to look, and saw, swinging along bravely as though they were marching to a ceremonial parade, a tiny column of men, led by the pipes and a drum, with the Drum-Major striding ahead. Silence fell as they came, and the drum tapped the pace for a moment as the pipers gathered their breath. Then, as they wheeled in towards us, they broke into Pitbroch o’Donuil Dhu with all the gay lilt of the Highlands and all the defiance and feeling any Scot can call out on his pipes. Smartly they march to attention, and halted as if on parade. To the strains of their regimental march the Camerons had come in to surrender”.

Reports in the British press made much of the symbolic march into captivity, not as a defeated battalion but under its Commanding Officer and headed by the pipes and drums. It was later reported that a young German officer who was unaware of the honour granted to the Camerons tried to order the marching troops off the road. He was upbraided by Lt-Colonel Duncan, with the Aberdeen Press & Journal anecdotally reporting that “The Colonel promptly knocked him down with a hefty right to the chin and then resumed his place at the head of his battalion”.

It was also reported that the numbers marching behind their Colonel would barely make a company, as most had elected to try their luck and make a break. One of these was a Lieutenant TA Nichol who in an interview with the News Chronicle in August 1942, after successfully making it to the Allied lines, reported that:

“Before it was light we made our way to a hole in the ground and lay up under a sheet of corrugated iron throughout the day. At dusk I had a look out with my field glasses. I could see little parties getting up out of holes all around us to make what distance they could during darkness. It did one’s heart good to see so many taking the chance. They were everywhere one looked, climbing out of their hideouts and stepping out for the frontier”.

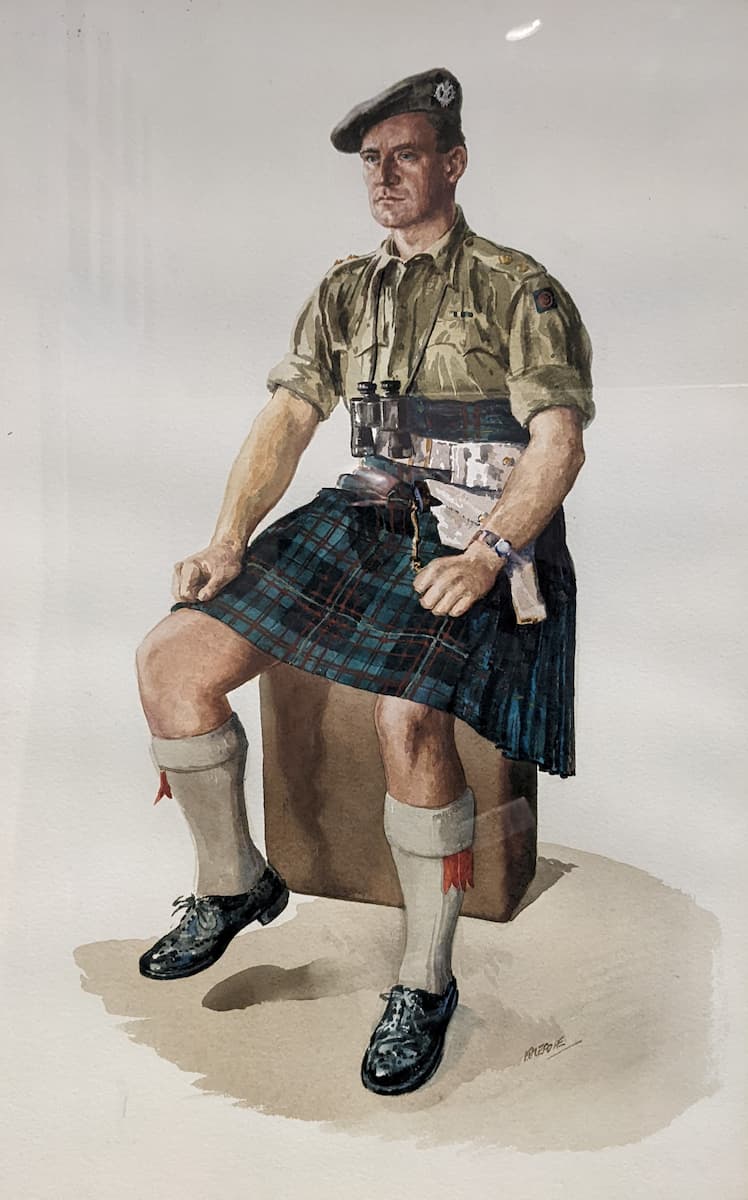

Lieutenant Nichol was awarded the MC for his exploits and his determined features are evident in a portrait by fellow officer and well know Scottish artist Ian Eadie which now hangs in The Highlanders’ Museum (Queens Own Highlanders Collection).

In the event, few of the 15 officers and 200 Cameron men who broke out from Tobruk made it across the 350 miles of desert to El Alamein, but two notable accounts, one by an officer and the other a private, are held in the museum archives and can be read here.

As the Commanding Officer, Lt-Colonel Duncan had no choice but to march into the prison cages at the head of his men. He was taken to a camp in Italy, where he briefly escaped but was recaptured and spent the rest of the war as a POW in Germany. On his release, he resumed command of the Battalion which went on to see post-war service in Austria and Italy, until it was disbanded in June 1948. Writing to him after the war, his Divisional Commander Major-General FIS Tuker of the 4th Indian Division wrote:

“I know the Battalion will never forget Tobruk but I also know that although that disaster reflects so ill on most, your battalion has not only nothing to be ashamed of but much to be proud. It is enough that everyone of the battalion did his best to get away; there was slender hope of this with almost the whole battalion on its feet”

As Tuker’s words allude to, the surrender of the 2nd South African Division and the loss of tonnes of equipment and over 25,000 men as POWs caused considerable controversy at the time, not least because many felt that had General Klopper been given clear orders to evacuate and pull back, most of the Division could have been saved. The Cameron’s heroic fight, brave attempts to escape and final show of defiance marching to captivity upheld the regimental honour and were used to successfully lobby for the battalion’s re-instatement to the Army list only six months later. Returning to Egypt in December 1943, the battalion arrived too late to see further action in North Africa but in February 1944 returned to active service in Italy at the Battle of Cassino.

By Craig Durham, Volunteer at The Highlanders’ Museum (Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection)