Charge of the Brass Hat Brigade

A Poem from the Archive

Tracing the biographical details of the people who wrote the cards, letters and poems held by The Highlanders’ Museum (Queens Own Highlanders Collection) can be a challenge. The surname can be a common one, making it difficult to narrow down from the millions of entries in the Forces War Records. Or it may just be a set of initials, recognised only by the author’s family. Some documents have no name attached at all.

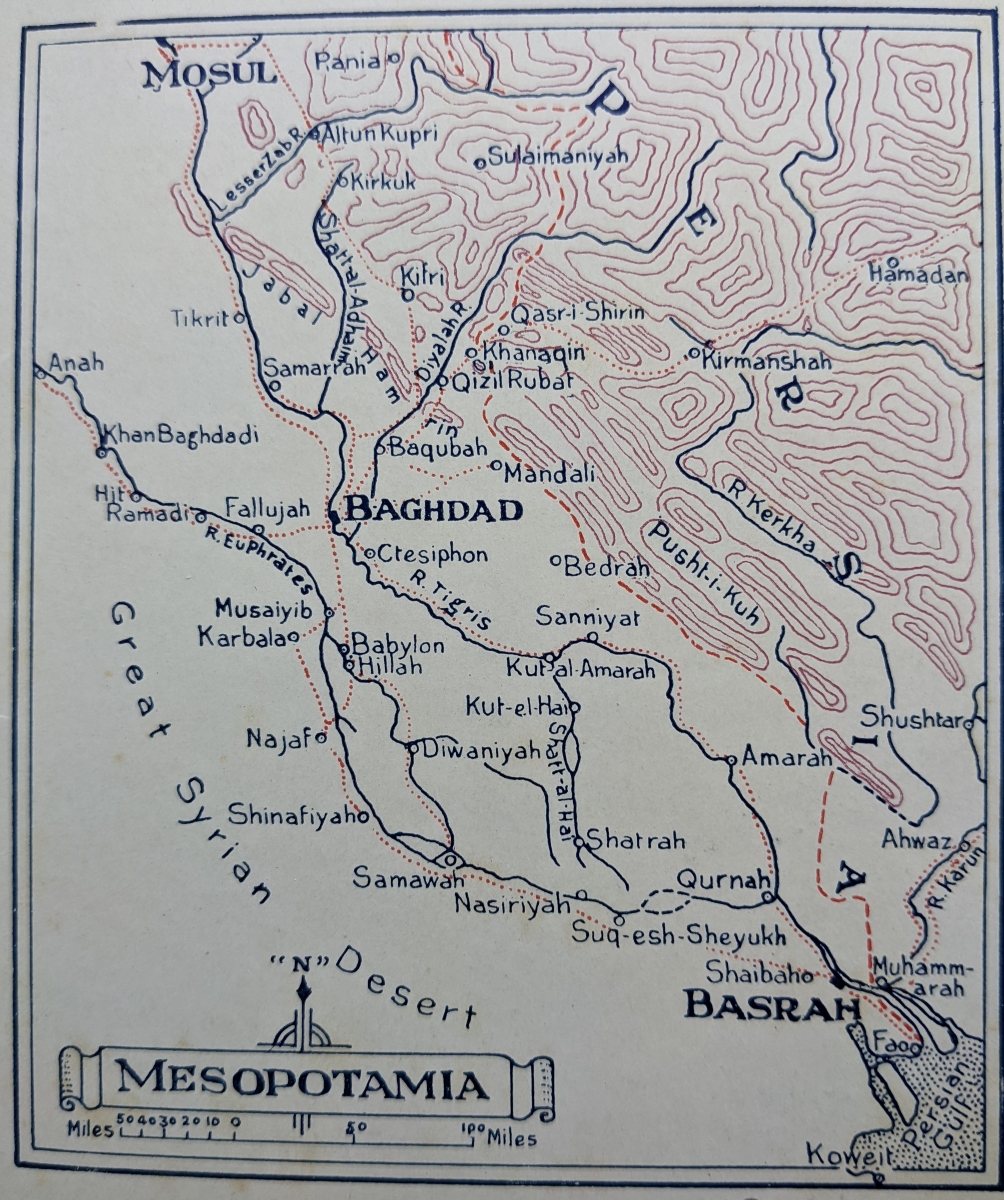

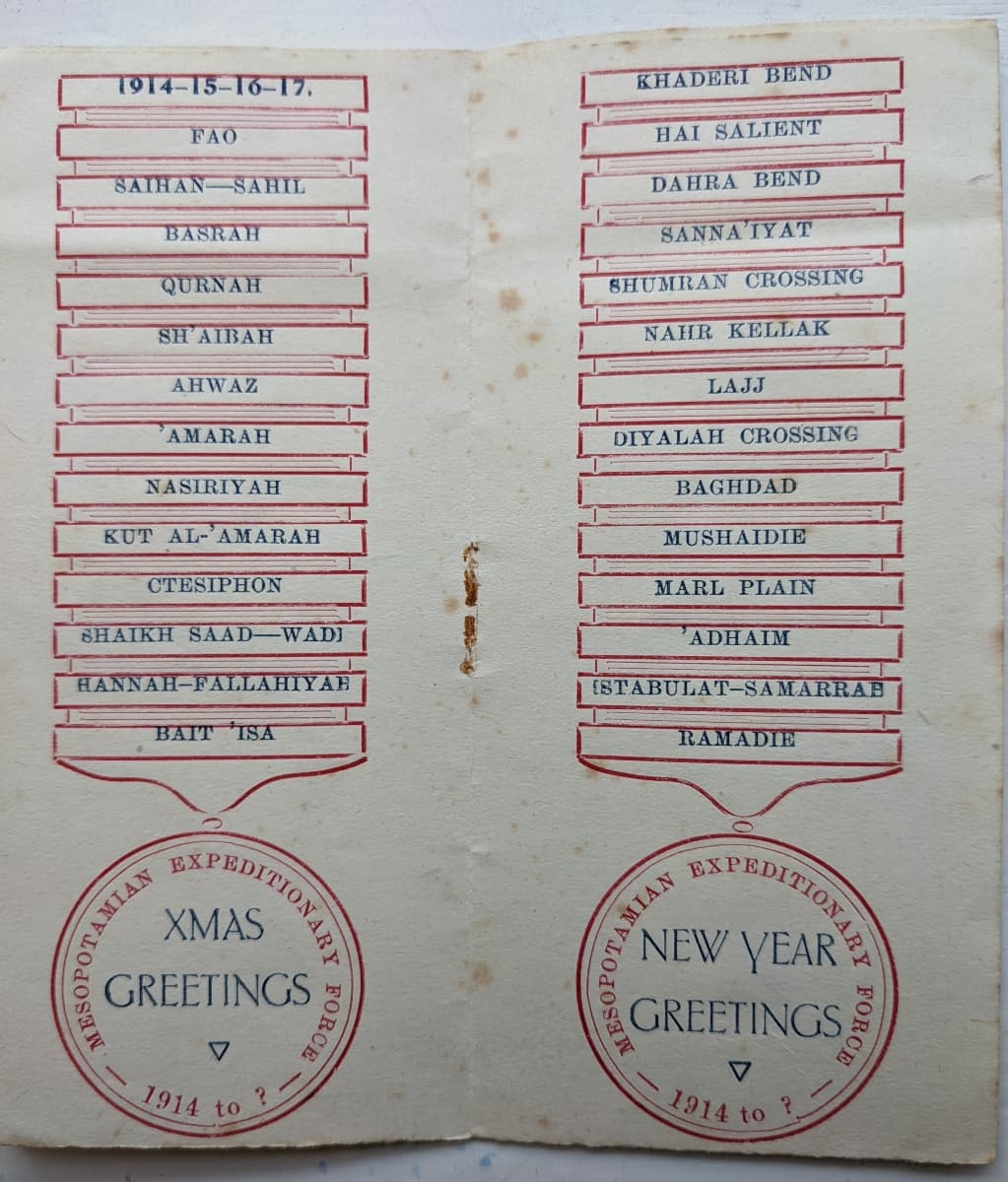

No such problem with the author of this month’s poem ‘Charge of the Brass Hat Brigade’. Thanks to an extensive collection of letters, photos and diaries donated to the museum by his widow in 1989, we know enough to write a book about Lieutenant WG Crask of 5th Battalion Seaforth Highlanders and later the 130 Machine Gun Company. We even have his hand drawn map of Baghdad on display in the museum.

William Gordon Crask was born on 10th May 1896, to John and Charlotte Crask of 132 Lumb Lane, Bradford. Upon enlisting in April 1915, he was sent to train with the 3/4th Territorial Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders then stationed at Dingwall. The Bradford Weekly Telegraph of 30 April 1915 carried a photograph of Crask with four fellow recruits about to board the train to Scotland. A few months later he received his Commission to the 5th (Sutherland & Caithness) Battalion and shortly after that transferred to the Machine Gun Corps, a new specialised part of the Army that was formed in October 1915.

After 18 months training and then as a machine gun instructor, he was posted to the Middle East in March 1917, where he remained until his discharge from the army in 1921. For most of that time he was in Mesopotamia, now Iraq, and witnessed first-hand the defeat of the Ottomans in 1918, the subsequent creation of the British Mandate for Mesopotania, and the 1920 Iraqi revolt against British rule. It was during this time that he received the Military Cross “for conspicuous gallantry and ability on the railway line south of Samarrah on 1st September 1920”. The Dundee Evening Telegraph reported that “During operations against a party of insurgents his armoured car was held up by damage to the line. He left his car under rifle fire, effected repairs to the line, and was thereby able to proceed down the line and cut off the retreat of a party of insurgents whom he held to their ground till our infantry delivered its attack and inflicted heavy casualties on them”. These armoured “cars” were specially adapted to run on the railway lines that connected the main towns within Iraq.

Crask regularly wrote home, separately to his father and mother. Letters to his mother generally describe the domestic aspects of life in the army – the food and accommodation, sports and social activities. Letters to his father are more direct, describing his military activities in some detail but also commenting on the politics of the day, and news stories from home. Of course, being British he regularly mentions the weather, in particular the searing summer temperatures which could reach as high as 48°C.

As well as the letters and diaries, he wrote several poems including “the A to Z of Mesopotania”, “Leave from Mesopotania” and “We are the Famous One Three Oh”. “The Charge of the Brass Hat Brigade” is a satirical parody of Lord Alfred Tennyson’s Charge of the Light Brigade lamenting the waste and bureaucracy emanating from General Headquarters (GHQ) during his time in the Middle East:

Charge of the Brass Hat Brigade

I

Half a lakh, half a lakh

Half a lakh squandered

Up to the Persian hills

GHQ wandered

Lured on by Hambro’s brains

Egged on by Julian’s pains

Pushed on by Lubbock’s trains

To the Shah’s stony plains

GHQ wandered

II

Charge for the camp he said

Was there a bill delayed?

No! though contractors knew

That someone had blundered

Ours not to calculate

Ours but to render straight

Forms “Cost Accounting” eight

Monthly, in triplicate.

Ours not to query

What GHQ squandered

III

Wars to the West of them,

Wars to the South of them,

Battles all around them

Volleyed and thundered.

Careless of tribes that kill,

Firmly they sat and still.

Dug in at Ser-a-Mil;

Then they came back,

But with half a Lakh squandered

IV

Honour the brave and fair

Wives who remained up there,

Breathing the common air,

No longer sundered.

Mixing with me and you,

Just as though GHQ

Might have been human too;

Why one camp would not do

All Karind wondered.

V

Honour the brave and bold

Taxpayer, young and old,

Who, although never told,

Paid by the hundred.

Think of the camp they made

Think of the water laid

on, and the fans arrayed,

Think of the bill we paid.

Oh! the wild charge they made

Gallant Brass Hat Brigade.

Half a Lakh squandered.

VI

Half a Lakh, half a Lakh

Half a Lakh squandered

Back from the Persian hills GHQ wandered.

Fed up with Hambro’s schemes.

Cured quite of Julian’s dreams.

Grateful for Lubbock’s means.

Back to our muddy streams

GHQ wandered.

By William Gordon Crask

The Brass Hat Brigade is a slightly disparaging term for high-ranking officials said to derive from the gold braid worn on their peaked hats, from where the similar phrase “Top Brass” derives. The Lakh is the common name for 100,000 Indian rupees, so “half a Lakh” would be worth around £5,000 today. The amount most likely chosen for the alliteration with “half a League” of Tennyson’s original, rather than any particular monetary value.

Hambro’s brains refers to General Sir Percival (Percy) Hambro, KBE, CB, CMG, Quartermaster General in Baghdad after the war and responsible for all transport and logistics. Lubbock’s trains is a reference to the Basra to Baghdad light railway that the British constructed to move equipment and stores up river, rather than rely on river transport on the Tigris and Euphrates. Julian’s pains is most likely a hubristic reference to the Roman Emperor Julian, who in 363 AD attempted to invade Persia by advancing down the Euphrates. He made it as far as Ctesiphon, just south of Baghdad, before being pushed back to Samarra where he was killed in a Persian ambush.

Of the two places mentioned in the poem, Karind, is most likely Kerend-e Gharb, a small town in Kermanshah Province, Iran, close to the border with Iraq. It is not clear what the reference to “dug in at Ser-a-Mil” means, as it can’t be found on any old Mesopotamian or modern map of Iraq. The British Army were involved in hundreds of skirmishes during their time in Iraq so Ser-a-Mil is perhaps a small, long forgotten village associated with that.

Crask returned to Britain in 1921 and married Julie Ida Tomlin in October 1925, at Southport, Lancashire. Interestingly, Julie had worked at GHQ in France during WWI so perhaps William’s sense of humour as demonstrated in this poem was what attracted her. William and Ida went on to live in Burnley, where he worked as a warehouse manager and then a civil servant in the Ministry of Labour. In 1942 he was promoted to the Weymouth office in Dorset, where he remained for the rest of his life.

William Gordon Crask died in 1983 at the age of 87, so never saw the return of British troops to Iraq in the first Gulf War of 1991 or the Iraq invasion of 2003, although he would certainly have been familiar with the place names and tribal politics of these more recent conflicts. If he were able to Google “British Army Cost Accounting” on some celestial internet today he would probably not be surprised to see that bureaucracy still reigns in the depths of the Ministry of Defence Logistics Framework and the Tri-Service Regulations for Expenses and Allowances JSP752. He might even feel inspired to write a 21st Century update to his poem. “Half a Latte” perhaps?

By Craig Durham, The Highlanders Museum (Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection) Volunteer