Drunk and Disorderly

Combating the demon drink in Queen Victoria’s army

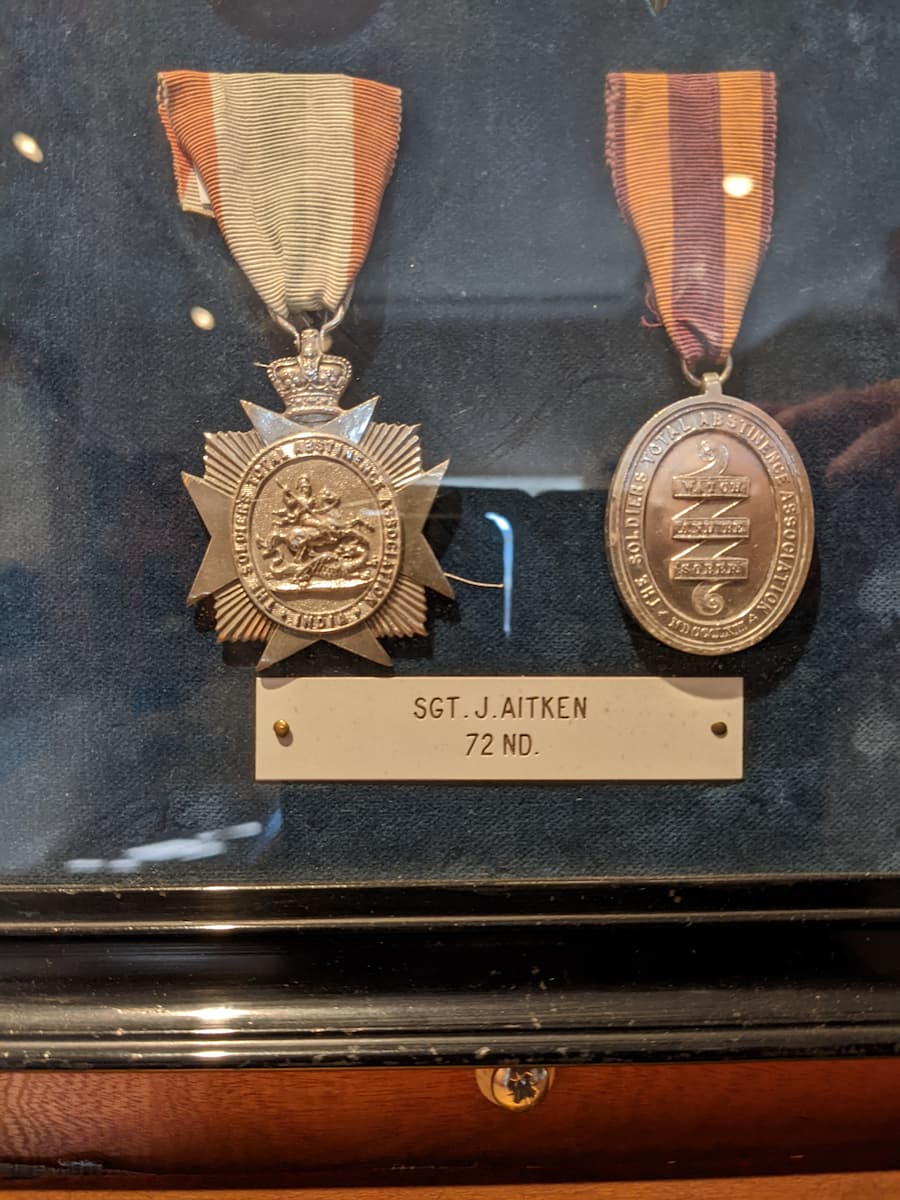

One of the more unusual medals amongst The Highlanders’ Museum’s extensive collection is the Soldiers Total Abstinence Medal, first awarded in August 1832 to those soldiers who kept a pledge to abstain from drinking. Despite thousands of these medals being issued during the subsequent Victorian and Edwardian eras, only two are in the possession of the museum. Both belonged to a Sergeant James Aitken, of the 72nd (Duke of Albany’s Own Highlanders) Regiment of Foot and were awarded along with his campaign medals for service in India during the 2nd Afghan War of 1878-80.

Highland soldiers and drinking have gone hand in hand since Sir Allan Cameron on his visit to Fort William to celebrate his newly commissioned 79th Regiment of foot in November 1793 “gave instructions to make that and subsequent days a carnival of hospitality – feasting and rejoicing without limit”. The previous month he had been in Aberdeen where according to a letter written by Colin Campbell of Barcaldine “Major Cameron, Erracht, has been at Aberdeen to get volunteers from Major MacLean. He gave a dinner to all officers of the Regiment and some of the Gentlemen of the town. When they had about two bottles of claret apiece, he calls for whisky to show them the Highland way of drinking; every man took off his glass but after that the bumper of whisky and the bumpers of claret went regularly round till Redcoat and Black were tumbling over one another. Some says he is only half mad but I say that he is wholly so for this Regiment of his has turned his brain”.

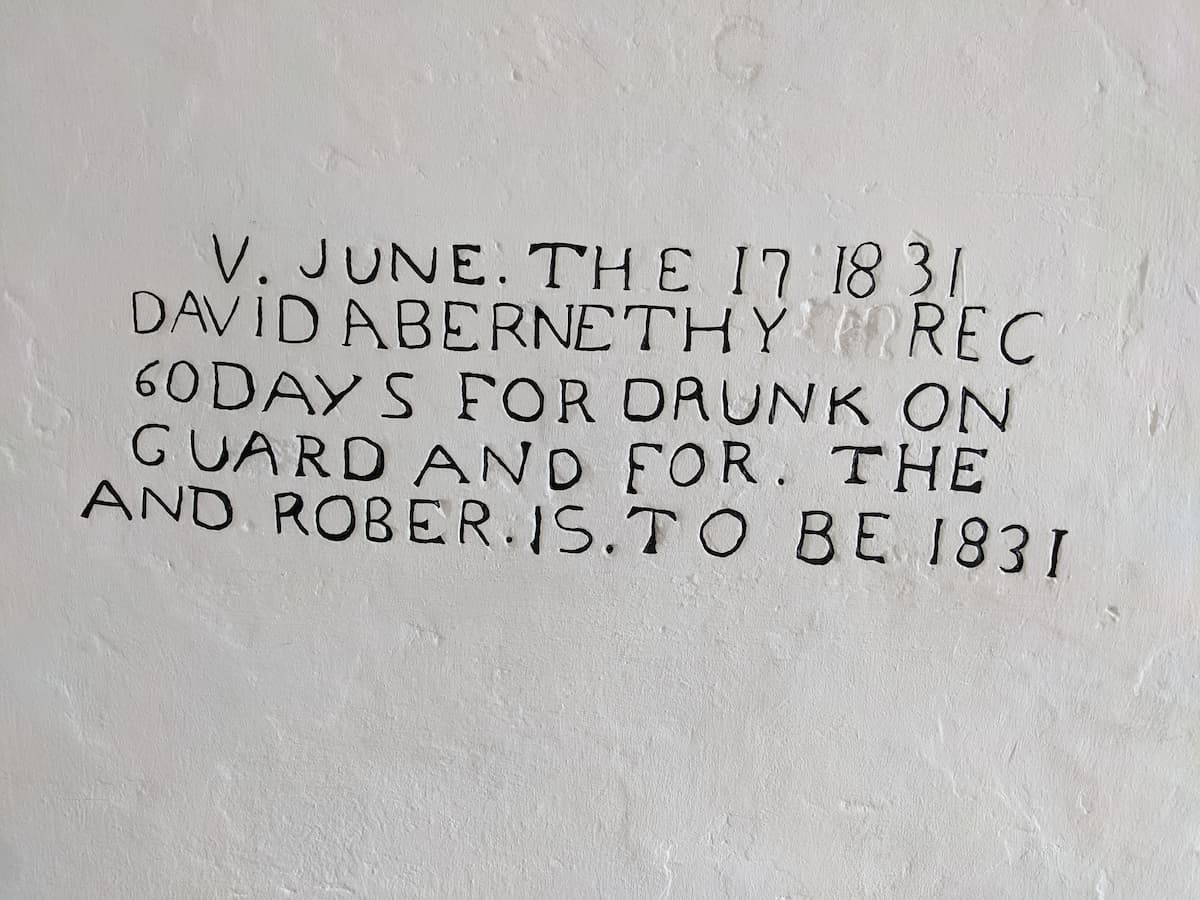

In those days it was common place to issue a ration of rum before battle to calm nerves, often followed by a drunken rampage through the defeated enemy camp or town once the defences were breached. Drunkenness was even worse amongst the home battalions, with the inns and taverns of the garrison town usually the only entertainment for the off-duty soldier. The Orders for the Assistance & Guidance of Non-Commissioned Officers of the 1st Battalion 79th Regiment issued in 1806 whilst garrisoned in Colchester, Essex, make clear the extent of the problem:

“The vice of drunkenness may be justly looked on as the chief source of almost every crime, and consequent punishment which occurs in a regiment; it debases the mind, enervates the body, and by creating at length a real want, which a soldiers pay is inadequate to supply, induces the commission of acts of dishonesty, and renders a man as contemptable in his character as he is from the debility of his body unfit for the noble profession of a soldier. Every means that can possibly be thought of, will therefore be adopted, to discountenance a vice of so infamous and dangerous a tendency; and so far from it ever being admitted an excuse for any fault, it will be esteemed an aggravation of it; and what might perhaps be overlooked on any other occasion, will never be pardoned when it has been the effect of drink. Drunkenness, on any kind of duty, will never be excused. A man known to be addicted to liquor, even though he has the good fortune to contrive that it shall not be the means of bringing him to punishment can, however, never be trusted: he will therefore be debarred from every sort of indulgence, particularly from furlows (sic) or passes, when his conduct as a drunkard would most probably bring discredit on the regiment.”

The problem continued throughout the first half of the 19th Century, particularly in India where there was little attempt to provide alternate recreation for the troops. This idleness, enforced by the climate and abetted by the availability of local servants; cheapness of alcohol, especial locally produced spirits; and perhaps most significantly an absence of safe drinking water all contributed to higher cases of drunk and disorderly in India than elsewhere.

The first Military Temperance Society was founded in Kolkata in India on 29th August 1832 and by 1836 it was reported that there was barely a regiment without a Temperance Society. In 1845 a United Military Temperance Society was formed in London but despite his initial support, the Duke of Wellington later banned Regimental Temperance Societies. Given his personal experience of the link between drink and ill-discipline, his reasons for the ban are not clear but it may have been that Regimental Societies were often set up under a quasi-religious umbrella and without the knowledge of the Lieutenant-Colonel, both of which had the potential to erode the authority of the regimental command structure. It was 15 years before Temperance activity resurfaced and in 1862 the Soldiers Total Abstinence Association was founded in India by Joseph Gregson (1835 – 1909), an English Baptist minister and army chaplain. The men were encouraged to sign ‘the Pledge’ to abstain entirely from alcohol, inspired by the motto ‘Watch and be Sober’. By 1865 the Association had 783 members across 24 branches within the Indian Army.

In 1879, the year James Aitken took part in the 2nd Afghan War and the occupation of Kabul, the Association’s annual report stated that “We have had a sufficient number of abstainers in the (Kabul) campaign to prove the value of abstinence from intoxicating liquors in a time of war. The abstainers were able to perform all their duties with less fatigue than their drinking comrades, and with a great deal more cheerfulness. If, instead of commissariat rum, and extra quantity of tea had been supplied to the men, many more would have remained true and loyal to their pledges”.

By 1885 the Army & Navy Gazette recorded that there were 11,257 abstainers in the Indian Army, almost a quarter of the rank and file, with newspapers reporting that “The regimental canteen is being replaced by the regimental coffee-shop, and the teetotalers tent has already been seen on the line of march. Time was when even a Bayard might accept it as part of the constitution and course of nature that the British soldier must have his beer and his tot of rum if he is to fight his country’s battles. Nowadays the British soldier has discovered that he can ‘war on water’”.

The Association’s report in the same year noted the following “Amongst other instructive figures Defaulters: 111 abstainers, 2593 non abstainers; Imprisoned by commanding officers: 2 abstainers, 280 non abstainers; Imprisoned by court-martial: no abstainers, 76 non abstainers; Reduced to the ranks: no abstainers, 31 non abstainers”.

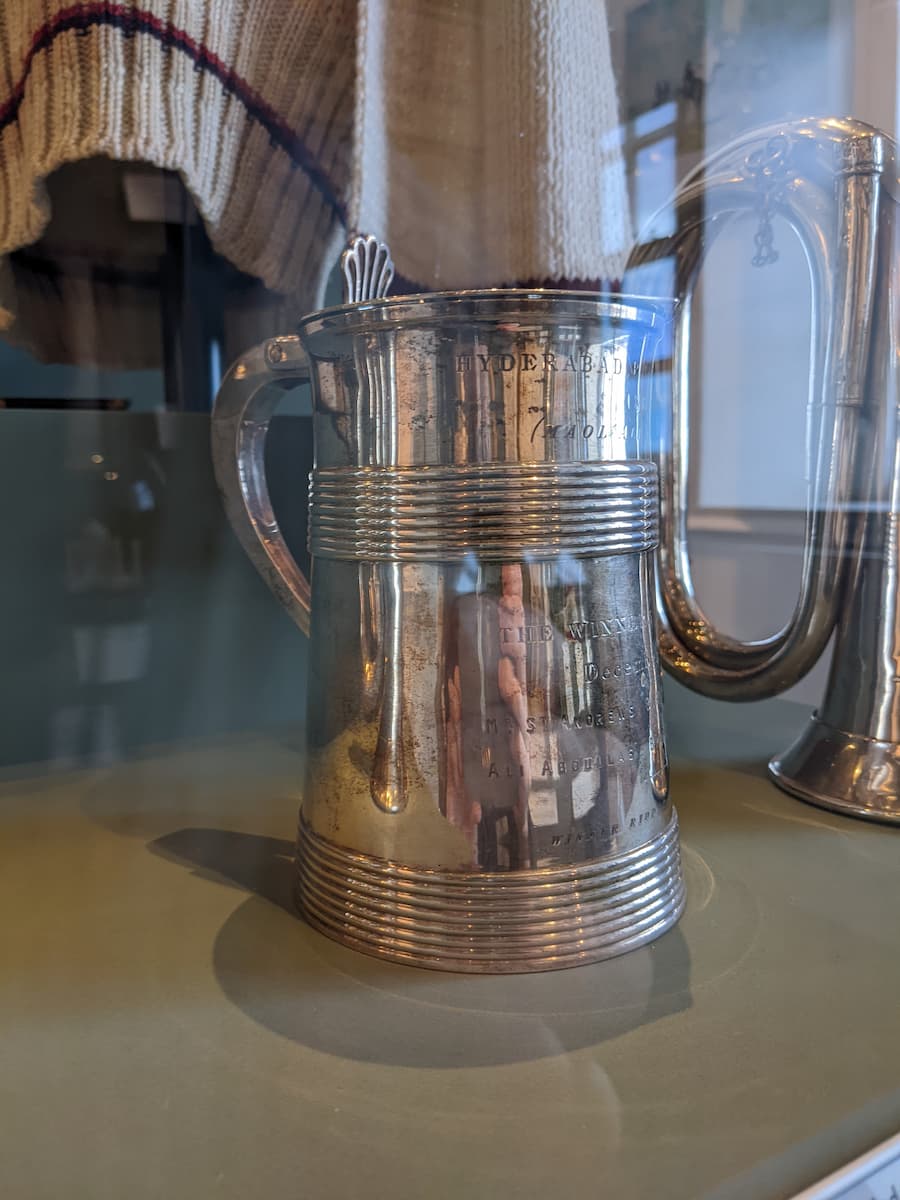

The ongoing success of the Soldiers Temperance Association in India led to the creation of the Army Temperance Association in 1893. It provided temperance institutes for its members, promoted regimental campaigns towards sobriety and sponsored a wide range of sporting activities. Ironically, many of the trophies awarded to the victors of these sporting competitions took the form of ceremonial drinking receptacles, no doubt filled and downed by the winning team in Sir Allan Cameron’s ‘Highland way of drinking’.

Military Temperance societies continued during the First World War. But according to the National Army Museum’s ‘Watch and Be Sober: The story of Army temperance’ the presence of temperance campaigners and other ‘do-gooders’ behind the lines in the rest areas of the Western Front was not always welcomed by officers or the men. Many understood that alcohol, along with tobacco, could play an important role in offering relief from physical and psychological stress. Indeed, both were issued to men as part of their rations.

The establishment of the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) in 1920, and their provision of recreational activities for service personnel, along with wider societal changes in attitudes towards alcohol, further decreased membership and the Army Temperance Association was finally disbanded in 1958.

As well as James Aitken’s abstinence medals, The Highlanders’ Museum has several sporting trophies in the form of ceremonial drinking receptables, although sadly not Sir Allan Cameron’s legendary whisky bumper. But we do have the museum’s own label single malt whisky for sale in the shop, and for the abstainers amongst you, a very nice refreshing ‘Blue Hackle’ tea.

By Craig Durham, Volunteer at The Highlanders’ Museum (Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection)