Seasonal Disorder:

The Siege of Burgos

Most visitors to the Highlanders Museum at Fort George come via the Historic Environment Scotland ticket office located on the outer defensive ravelin and separated from the main fort by a deep, wide scarp, or dry ditch moat. Today the ravelin and ditch provide a pretty effective barrier to anyone trying to sneak in without paying, and back in the 18th Century these structures served an even more formidable obstacle, with anyone attempting unlawful entry likely to pay with their lives. Which makes it all the more extraordinary that in September 1812 the 79th Highlanders in the Peninsular army successfully attacked a similar defensive structure at the town of Burgos, in northern Spain, in what was one of Wellington’s rare errors of judgement.

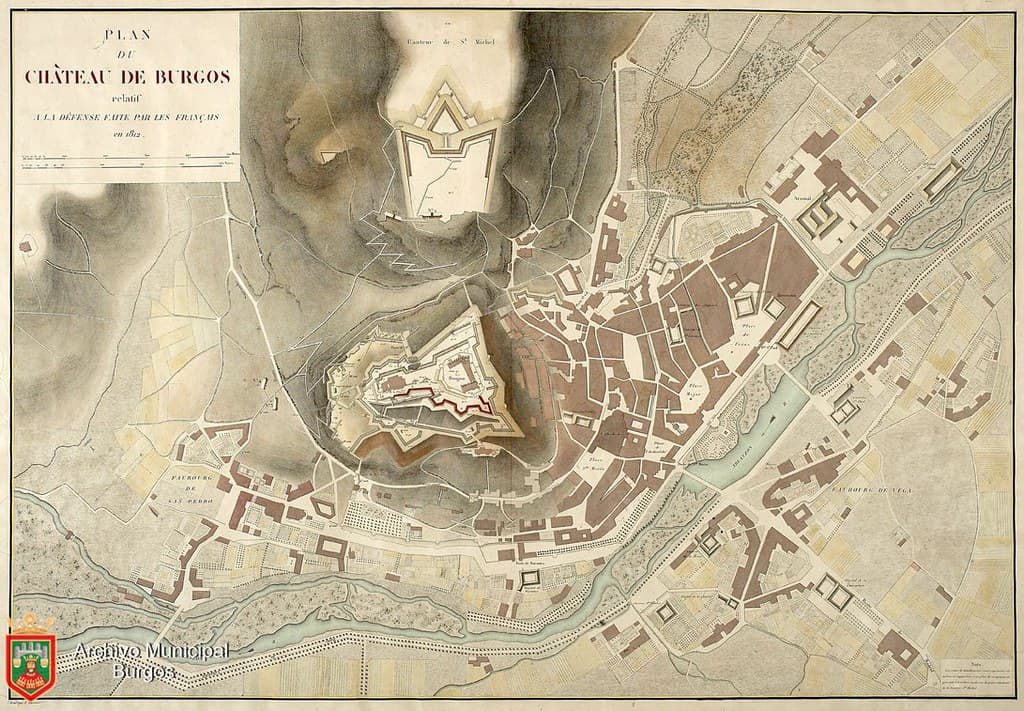

Up until then 1812 had been a very successful year for the Duke, with the storming and capture of the border fortresses of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz in January and April, followed by a stunning victory at Salamanca in July and the occupation of Madrid the following month. Despite this success, the allies were vulnerable to a co-ordinated French counter attack and so Wellington decided to maintain the offensive and push on, driving the French north of the Duero towards the Pyrenees. Entering the town of Burgos on 18th September, he found the citadel that commanded the heights just north of the town defended by 2,200 well-armed and provisioned men under General Dubreton. Some 500 yards to the north east of that on another hill stood the redoubt of San Miguel, also known as the horn-work, which had been built to a similar design as the Fort George ravelin.

“… the 79th Highlanders in the Peninsular army successfully attacked a similar defensive structure in northern Spain, in what was one of Wellington’s rare errors of judgement.”

The plan was to capture the horn-work first and use that as a position to bombard the main citadel, using the same tactics that had captured the Greater Teson overlooking Cuidad Rodrigo back in January. A firing line was to overwhelm the defenders from the crest of the counterscarp while another force climbed down into the ditch and ascended the far side. This main attack became confused and failed, but Major Edward Somers Cocks, in command of the light companies of the 1/24th, 1/42nd and 1/79th converted what was supposed to be a false attack on the gorge on opposite side of the horn-work into a real assault, as described in the Historical Record of the Cameron Highlanders:

“At the appointed hour the troops moved to the assault. The light companies, on arriving at the gorge of the work, were received with a withering fire through the loopholes in the palisading, which caused very heavy loss. Undismayed by this, however, the men rushed in, and without waiting to use their felling axes and ladders, lifted the foremost men over the palisades. The first man to enter the horn-work was Sergeant John McKenzie of the 79th. He was assisted over the palisades by Sergeant Masterton McIntosh, receiving a bayonet wound through his arm as he reached the ground inside. He was closely followed over by Major Cocks, Sergeant McIntosh and other members of the storming party. In this manner, and with the aid of scaling ladders, the light battalion was in a very few minutes inside the work, when a guard of twelve men, under Sergeant Donald McKenzie of the 79th was at once placed upon the gate. A charge was then made upon the garrison, and a desperate struggle ensued. In their efforts to escape the French dashed for the entrance held by Sergeant McKenzie and his men, rushing past them in full flight in the direction of the castle. Sergeant McKenzie and his party behaved with the greatest bravery in their efforts to stem this rush and arrest the wild career of the fugitives. He himself was severely wounded, whilst bugler Charles Bogle of the 79th was afterwards found dead in the gate alongside the body of a French soldier, the sword of the former and the bayonet of the latter thrust through each other’s bodies!”

After the capture of the horn-work, the measures taken to reduce the Citadel consisted in a series of assaults, ending, with one exception, in repulses owing to a lack of heavy siege artillery. In one of these attacks Major Andrew Lawrie of the 79th was killed while entering the ditch and in the act of encouraging his storming party to assault by escalade. Upon another occasion Major Cocks met a similar fate while rallying his men in the trenches during a night sortie by the French garrison.

Lord Wellington was deeply affected by the death of Major Cocks and wrote in a personal letter of condolence to his father, Lord Somers “Your son fell, as he had lived, in the zealous and gallant discharge of his duty…I was highly sensible of the merits of your son, and I most sincerely lament his loss”.

Besides Majors Lawrie and Cocks the Cameron Highlanders in various operations during the siege had two sergeants, one drummer and 29 rank and file killed and a further two officers and 17 rank and file died of wounds. Total allied losses throughout the siege were 2,059; French casualties were less than a third of that.

On 21st October, with French reinforcements now on their way to relieve the siege, the British broke camp and commenced a hasty and somewhat disorderly retreat back to Portugal, crossing the border on 19th November 1812 and going in to winter quarters, after what the generally cautious Wellington famously described as “the worst scrape I ever was in”.

By Craig Durham, Volunteer at The Highlanders’ Museum (Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection)