Of Arms and Men I Sing

The Seaforths Pioneer – zem zem

Zem Zem Anthology #2

Digging trenches, laying roadways, and building fortifications has been a part of the soldier’s life since long before Hadrian’s legionnaires built his wall, and formalised as a distinct discipline within the British Army in 1716 when the Corps of Engineers (later the Royal Engineers) was formed. This was an officer only Corps, with labour provided by either Articifer companies of specialised civilian trades, or regular infantrymen. In 1787, the Corps of Military Articifers was created to provide a dedicated source of labour, consisting of NCO’s and privates under the command of the Royal Engineers. Throughout the course of the 19th Century, wherever the Army marched, these men followed, building or blowing-up whatever bridges and barricades the General Officer Commanding demanded.

At the outbreak of WWI, the role was seen no differently, but by November 1914 it was obvious that the scale of trenches, fortifications, road and railways required could not be built by Royal Engineers and regular infantrymen alone. The solution was to create so-called Pioneer battalions, one assigned to each Division, to support the Royal Engineers and relieve the infantry from some of its non-combatant duties.

The War Office decreed that at least 50% of a Pioneer battalion strength should be made up of men used to working with a pick and shovel, and the other 50% should have a recognised trade such as bricklaying or joinery. Adopting a badge of crossed rifle and pick, the role of these new units was defined as one of fighting infantry, capable of providing ‘organised and intelligent labour’ for engineering operations. *

* Pioneer Battalions of the Great War K.W.Mitchinson, Published by Pen and Sword, 1997.

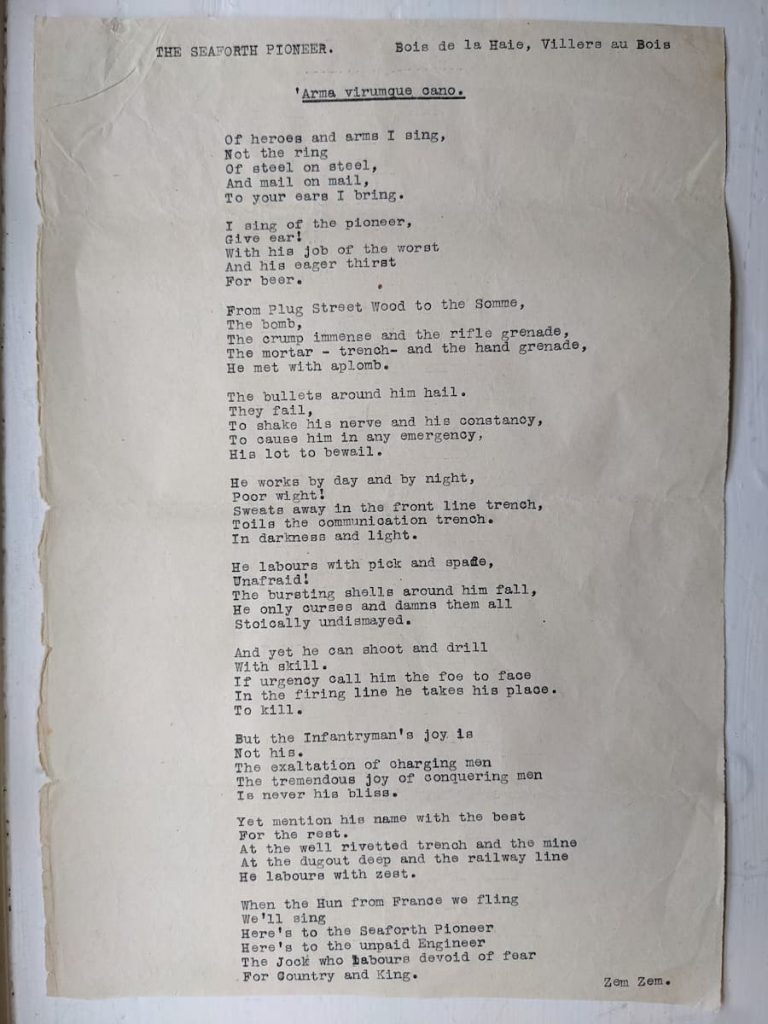

THE SEAFORTH PIONEEr

(‘Arma virumque cano)

Of heroes and arms I sing,

Not the ring

Of steel on steel,

And mail on mail,

To your ears I bring.

I sing of the pioneer,

Give ear!

With his job of the worst

And his eager thirst

For beer.

From Plug Street Wood to the Somme,

The bomb,

The crump intense and the rifle grenade,

The mortar – trench – and the hand grenade,

He met with aplomb.

The bullets around him hail.

They fail,

To shake his nerve and his constancy,

To cause him in any emergency,

His lot to bewail.

He works by day and by night,

Poor wight!

Sweats away in the front line trench,

Toils in the communication trench.

In darkness and light.

He labours with pick & spade,

Unafraid!

The bursting shells around him fail,

He only curses and damns them all

Stoically undismayed.

And yet he can shoot and drill

With skill.

If urgency call him the foe to face

In the firing line he takes his place.

To kill.

But the Infantryman’s joy is

Not his.

The exaltation of charging men

The tremendous joy of conquering men

Is never his bliss.

Yet mention his name with the best

For the rest.

At the well rivetted trench and the mine

At the dugout deep and the railway line

He labours with zest.

When the Hun from France we fling

We’ll sing

Here’s to the Seaforth Pioneer

Here’s to the unpaid Engineer

The Jock who labours devoid of fear

For Country and King.

Zem Zem

Bois de la Haie, Villers au Bois

(undated)

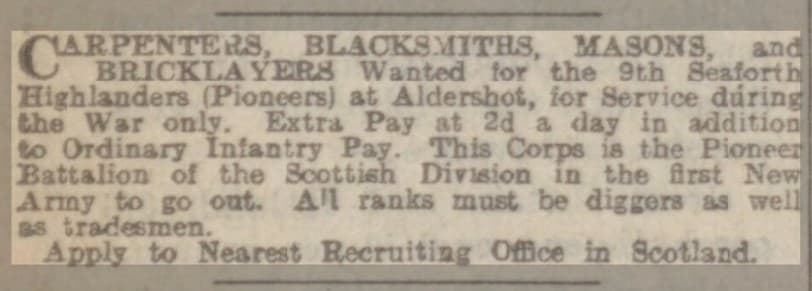

Raised in September 1914, 9th was the last of the Seaforth Battalions to fill Lord Kitchener’s New Army groups. Initial training was undertaken at Fort George, mainly by old NCO’s as there were very few regular officers available. The battalion had been raised as infantry but at the end of November it transferred to Aldershot where it was designated the Pioneer battalion of the 9th Scottish Division. This meant beefing up its pioneering skills, necessitating a recruitment drive typified by an advert in the Dundee People’s Journal classifieds in January 1915:

“CARPENTERS, BLACKSMITHS, MASONS and BRICKLAYERS wanted for the 9th Seaforth Highlanders (Pioneers) at Aldershot, for service during the War only. Extra pay at 2d a day in addition to Ordinary Infantry Pay. This Corps is the Pioneer Battalion of the Scottish Division in the first New Army to go out. All ranks must be diggers as well as tradesmen”.

The higher pay than ordinary infantry was a recognition that Pioneers were skilled artisans and tradesmen, not just labourers. Although a welcome bonus, the extra 2d per day was still 8d less than paid to Royal Engineer sappers, even though they often worked side-by-side on the same job, and hence the line “Here’s to the unpaid engineer” in the poem.

Typical of the men who answered the call were John Herron, a gardener from St Andrews, Robert Chalmers, an engine driver from Wemyss, and Henry Nairn, a mason from Newburgh. At 31, George Coyle, an oil shale miner from Winchburgh, was one of the older recruits. He was a keen amateur boxer and supplemented his income by doing stand-up comedy in the social clubs and welfare halls of Mid Lothian, under the stage name “Dorothy” Knowles.

The officers too were recruited from engineering professions. Lieutenant G C Griffin and Captains J S Turcan and F L F Kelty were Civil Engineers, the latter having worked for the Egyptian Government on the first Aswan (low) Dam. Captain, later Major, W E Furneaux had previously served as a Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers during the Boer War before joining the Seaforths in February 1915. Prior to re-joining he had worked as an engineer for the Stanley Steam Car company in Gateshead and must have had an extremely tough constitution; only three years before, he had been badly injured when one of the company’s cars crashed into an empty coal cart during a trial run.

The 9th Seaforths moved to France in May 1915 and first went into the trenches at Bailleul, close to the Belgium border. The West Lothian Courier printed a letter from the now Lance Corporal George Coyle to his wife, written in August 1915, in which he shares some of his experiences of that first three months:

“I have travelled a great deal since I left Bologne. We marched four miles to a station, and then got into cattle trucks, 29 of us in each, and some had to stand all the way for 15 miles, at slow progress. We have had some great marches, doing from 30 to 40 miles, and the heat is terrible through the day. I may say we have seen more of the firing line than any of Kitchener’s men that came out in the Division, as we are a Pioneer Battalion, and when any of the trenches have to be repaired we have to go and do it. I went through a course of bomb making and throwing in England, little thinking I would be called upon so soon to perform out here. The Captain of the Worcesters says I am the finest grenade thrower he has seen, and he has been out since the war started”.

In September, the Division moved to Cambrin and Vermelles in preparation for the first major offensive planned to test the effectiveness of the New Army troops: the Battle of Loos. The 9th Seaforth supported the attack on the Hohenzollern Redoubt and the Fosse, cutting new trenches to connect the forward British lines to the captured German trenches. The battalion earned commendation for its excellent work under heavy fire, often required to fight as infantrymen as well as work as pioneers.

The battalion spent the spring of 1916 at Oosthove Farm, then moved to Bray-sur-Somme in preparation for the Somme offensive. Their war diary entry for the week 12th – 19th June gives a flavour of the work required:

War Diary, 12 – 19 June, 1916

A Coy engaged in reclaiming WEST AVENUE and SUPPORT AVENUE, erecting dug outs at CUMBERLAND ST. and digging new trench DUKE ST.

B Coy engaged on continuation of STANLEY AVENUE, clearing MARICOURT-MONTAUBAN ROAD of fallen trees and clearing trench running parallel with road. Bridges were made over three trenches crossing the road. Afterwards the Coy was engaged in constructing slit trenches in BEDFORD ST and reclaiming WESTON AVENUE.

C Coy working on Assembly trenches, making camouflage and laying over trenches, cutting top of new assembly trench as guide for Infantry working parties. In addition, they constructed three splinter proof dug outs for Batt Headquarters in assembly trenches.

D Coy constructing dug outs 22ft deep in CEYLON WOOD for use as a telephone exchange, constructing large dug outs in TALUS WOOD and U works, PERONNE for holding water tanks. In addition, the Coy had a party working on traverses in WEST AVENUE.

The nature of Pioneer work was such that the men were scattered in company or even platoon strength all along the front of the Division, according to where its services were required. During the Battle of the Somme the 9th Seaforth took part in difficult fighting at Longeuval and Delville Wood, and in the attacks on Butte de Warlencourt. They briefly occupied village of Montauban until relieved on 20th July. Other tasks included road repair, consolidating captured positions, and constructing strongpoints. Although pioneers were not expected to lead the attack, they did follow closely behind and were often exposed to enemy counter attack, at which the Germans were very effective. The battalion’s casualties during July 1916 were 16 killed and 142 wounded.

In August, the battalion retired to Boie de la Haie, a wooded area in the grounds of the Chateau of the same name and where the poem The Seaforth Pioneer was written.

By Craig Durham, Volunteer at The Highlanders’ Museum (Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection)