Pistols at Dawn

The curious practice of duelling in the army

Despite the Fort George ramparts bristling with canon, the only weapons ever fired in anger on the Ardersier promontory are the set of duelling pistols on display in The Highlanders’ Museum. In this blog we explore this peculiar 18th Century practice of defending ones honour.

Although illegal, duelling was wide spread during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, particularly amongst army officers. Unlike on the continent, where sabres were the weapon of choice and usually only a trace of blood had to be drawn to satisfy both parties, in Britain pistols were much more common, and deadly.

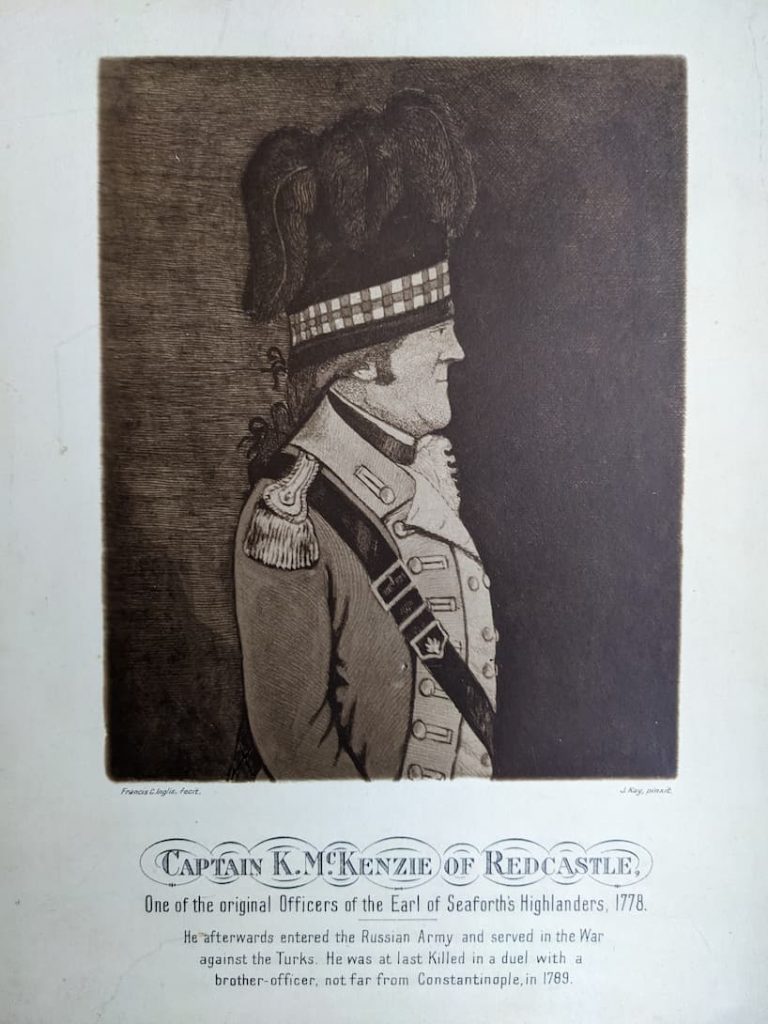

The 78th (Seaforths) were no strangers to the practice. One of their original officers, a Captain Kenneth Mackenzie, 8th Laird of Redcastle, was by all accounts a touchy and ill-tempered man and an habitual dueller who after three fights with brother officers was bought to trial by court martial in 1779. In the court proceedings the trivial origin of a duel between Redcastle and a Lieutenant Stuart was that “they threw wine at each other and mustard”.

Redcastle continued his quarrelsome ways after resigning from the Regimental list in 1784. According to the History of the Mackenzies*, he went abroad in the Russian service and was killed in 1789 near Constantinople (now Istanbul), in a duel with a Captain Lee, master of a merchant ship. According to an eye witness report in the Caledonian Mercury, the two men “quarrelled over a bottle at a French tavern in Pera, where (Captain Mackenzie) was very ill used. Upon 28th March, Captain Mackenzie, having met with Captain Lee in the public street of Pera, spit twice in his face, shaking his cane over his head, and using some harsh epithets”.

(* History of the Mackenzies, with genealogies of the principal families of the name; Alexander Mackenzie; 1894; page 542)

The museum has copy of a sketch of Mackenzie purportedly by the Edinburgh caricaturist John Kay. The sketch itself has some notoriety and was confirmed to be an ingenious but misleading composite print by Major Scorbie Mackay, editor of Caber Feidh in the 1930’s.

Closer to home, the pair of duelling pistols on display in The Highlanders’ Museum were used in a duel between Colonel Alexander MacDonnell of Glengarry and Lieutenant Norman MacLeod, both 42nd Foot (the Black Watch), fought on the links between Ardersier and Fort George on 3rd May 1798. Like many duels the cause was over the affections of a lady: the Colonel had been pestering a Miss Forbes for the last dance at a ball held in Inverness two days earlier, and Lt MacLeod had upbraided him for it. There followed an exchange of words, Colonel MacDonnell struck Lt MacLeod with his stick who responded by drawing his dirk and challenged the Colonel to a duel at a place called the Longmans (now the site of Inverness Caledonian Thistle’s stadium). This was thwarted by the arrival of the local magistrate, whereupon Lt MacLeod and his second, Captain Campbell, repaired to Sinclairs Inn on the road to Fort George and issued a further challenge to meet on the links there.

Despite the efforts of their fellow officers to settle the matter amicably with an apology from the Colonel, Lt MacLeod insisted that he give up his stick too, which the Colonel deemed a step too far and refused. Thereupon pistols were loaded, the protagonists took up positions eleven paces apart and according to a detailed report in the Scots Magazine “at the words ‘Are you ready’ Lt McLeod levelled his piece, but Glengarry did not bring his down till the word Fire was given; that they fired nearly at once, and the witness (Major McDonald, Glengarry’s second) perceived Lt McLeod wounded, but he did not fall; that Captain Campbell said the wound was only a scratch”. At the insistence of Major McDonald the two men apologised to each other and shook hands, and Lt McLeod was taken to Fort George where the surgeon removed the ball from under his right armpit.

After appearing to recover, his condition deteriorated and he died on 3rd June. Colonel MacDonnell was subsequently tried for murder, but was acquitted due to “the anxious desire latterly manifested by (the Colonel) to settle the matter amicably and prevent proceeding to extremities by making an apology”.

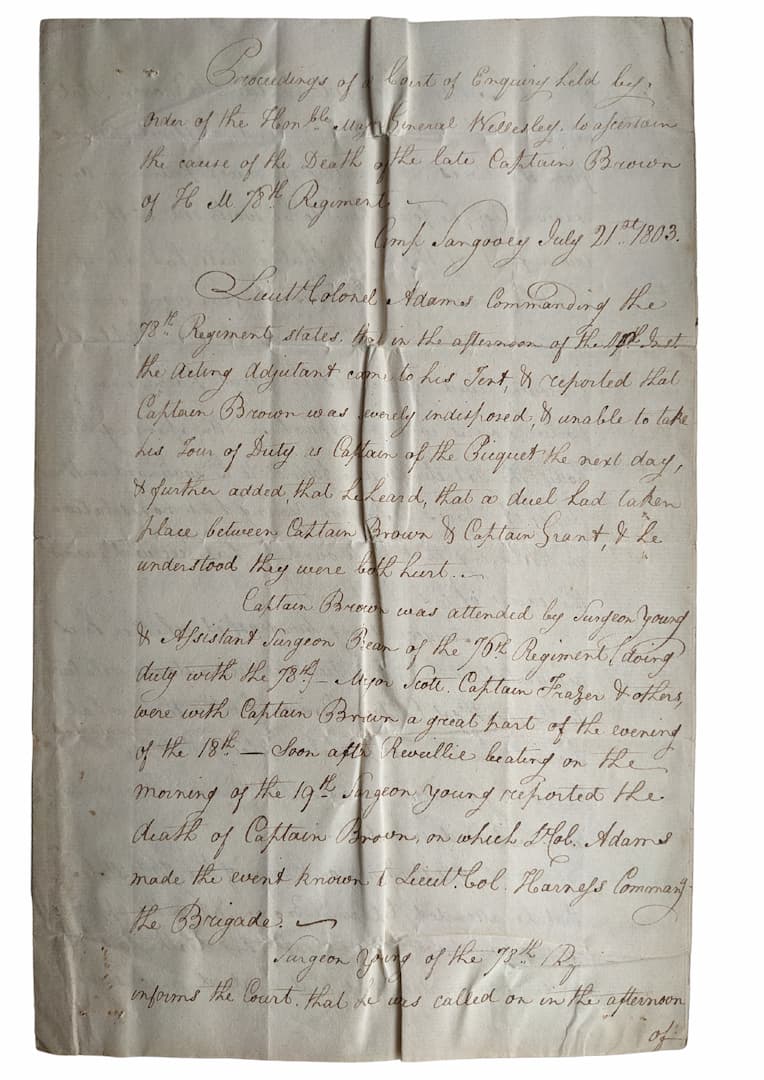

Issuing a challenge to a duel ‘to gain satisfaction’ was a matter of honour if one felt wrongly rebuked or insulted. The reasons were often quite petty, none more so than that recorded in one of the oldest documents in The Highlanders’ Museum archive, Proceedings of a Court of Enquiry held by orders of the Hon. Major General Wellesley to ascertain the cause of the death of the late Captain Brown of H.M. 78th Regiment, held at Camp Sangooey, in India, on July 21st 1803.

According to the proceedings, Lieutenant Colonel Adams, Commanding Officer of the 78th, first knew of the affair when his adjutant reported that “Captain Brown was severely indisposed and unable to take his tour of duty as Captain of the Piquet the next day”. The Regimental Surgeon confirmed that he had been called on the afternoon of 18th July to visit Captain Brown, and that “he found him sitting on the ground a short distance from the lines, apparently in much pain. On examination, he found him to be wounded in the lower part of the belly, that a ball had entered a little above the right groin and came out nearly the same place on the opposite side. Captain Brown lived afterwards in great pain nearly 12 hours when he expired”. The Surgeon confirmed that the cause of death was the bullet wound and that Captain Brown had received the wound in a duel with Captain Grant.

It was left to Major Scott of the 78th to explain the circumstances that lead to the fatal encounter, as told to him by the dying Captain Brown: “He stated an evening or two before Captain Grant had sent for a piper belonging to his (Captain Brown’s) Company and employed him without his leave or consent. Next morning on parade Captain Brown, taking Captain Grant aside, mentioned the circumstance of his sending for the piper, and said: I request, Captain Grant, that should you on another occasion wish to employ a man of my Company, you will let me know; to which Captain Grant said ‘you are not Commanding Officer of the Regiment and I will not sent to you’. Captain Brown then turned aside and said ‘it is a boyish trick altogether’. Soon after Captain Grant sent an officer to Captain Brown desiring he would apologise for what had passed on parade. Captain Brown declined to make any apology. The same officer came again to Captain Brown, desiring he would consider the matter and that unless he made the desired apology, he (Captain Grant) would call a meeting of officers of the regiment and expose him. Captain Brown then sent his answer that he would make no apology and should there be any meeting of the Officers of the Regiment on the business the whole should be laid before the Honourable Major-General Wellesley”.

At this point Captain Brown became much exhausted and the Surgeon recommended that he rest, so the exact circumstances of the duel are not recorded. Strangely, the Court of Enquiry did not call for Captain Grant’s side of the story, possibly so as not to prejudice any subsequent court martial.

There is no record of any further action taken, and most likely the whole affair was brushed under the carpet. Major General Wellesley, later to become the Duke of Wellington, was at the time planning an attack on the hill fortress of Ahmednagar, as part of the campaign to subdue the Northern Maharajahs in the Second Mahratta War of 1803, so no doubt had more important matters on his mind.

By Craig Durham, Volunteer at The Highlanders’ Museum (Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection)