To my Jerkin

A poem from the archive

To My Jerkin is another of Zem Zem’s rather whimsical poems about a seemingly nondescript item of British Army issued equipment – in this case the ubiquitous leather jerkin. The poem is undated, but contains several classical references and so possibly written in early 1918, by which time Zem Zem was serving with the 138th Field Ambulance in Northern Italy.

For a campaign that was supposed to be over by Christmas, the British Expeditionary Force was chronically underprepared for the icy cold weather that blasted Northern France during the winter of 1914-15. The goat and sheepskin pelts hastily issued to the troops in 1915 were found to be totally unsuitable for trench warfare and gave the men the the slightly outlandish appearance of Klondike fur trappers. The 9th Seaforths diary entry for 24th October 1915 doesn’t comment on that but simply states: “Weather very wet and cold, roads in bad condition. Braziers issued to troops, also goatskin and sheepskin jackets”.

TO MY JERKIN

No silken web of Tyrian hue [1],

No costly garb of Flemish loom [2]

Can woo one from thee comrade true

I’ll wear thee till the crack of doom.

In vain let chilly Borras [3] blow,

Or whirling snowflakes fill the air,

In vain let icy torrents flow,

Or mud spread out its viscous sorare [4].

For snug and warm in thy embrace

I live and laugh the world to scorn,

I look old Hyems [5] in the face,

Of all his arctic terrors shorn.

The “British Warm” gets spongy – wet,

The ‘greatcoat’ flaps about my feet,

No choicer garment can I get

Than thee, my jerkin, short and sweet.

They say adhesions firm and strong

Bind thee to me through constant wear,

T’is true, affection felt for long

Will form adhesions hard to tear.

T’is an amorphous trunk they cry,

And by an ugly want impaired,

But Milo’s Venus [6] doth deny

A want that with herself is shared.

Long may I live enwrapt in thee,

By thee kept healthy, warm and clean,

In peace and in adversity

Clad in my jerkin’s ambersheen.

[1] Possibly a reference to Tyrian purple, a reddish-purple natural dye extracted from sea snails and originally from Tyre, Lebanon. The dye was highly valued, hence the association of purple cloth with emperors and royalty.

[2] Flemish Broadcloth is a dense, plain woven woollen cloth. The unique milling process gave a highly weather-resistant, hard-wearing cloth favoured by uniform makers in the 19th Century.

[3] The Borra is a north-easterly wind that brings cold air down from to mountains to the warmer coastal fringes of the eastern Adriatic.

[4] An Italian verb meaning to spread out (literally ‘expose to the air’)

[5] Hyems, or Hiems, is the Latin word for winter, sometimes meaning the personification of Winter.

[6] The Venus de Milo statue of Aphrodite, on display in the Louvre, is famously missing her arms.

By 1916 British troops were instead issued with the leather jerkin. Designed to protect against the cold and elements, without inhibiting freedom of movement, the jerkin proved popular with officers and men alike. Writing about his much-loved jerkin, Zem Zem notes “By thee kept healthy, warm and clean” a comparison to the goatskin jacket, which the jerkin replaced, that was notorious for attracting lice and smelt awful when damp.

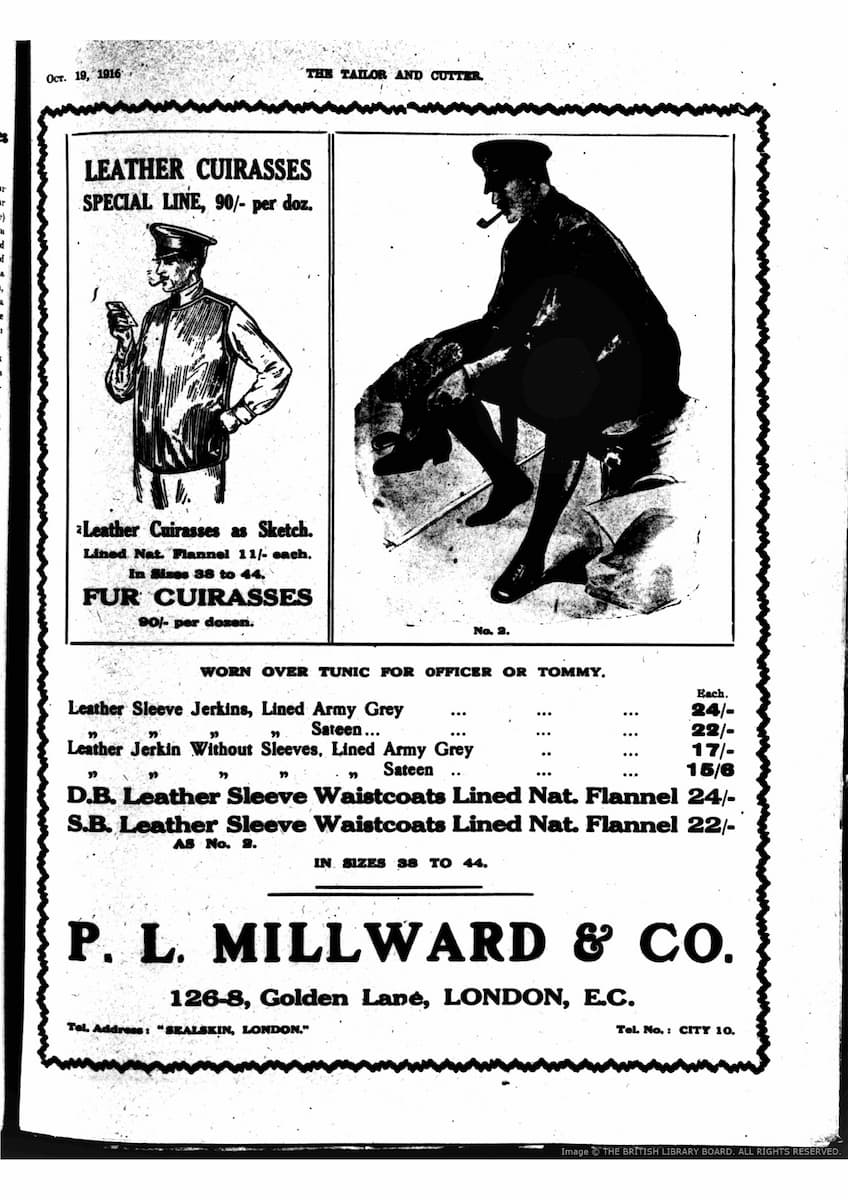

However, the only officially approved overcoat for officers was the so-called British Warm, the large, heavy woollen coat that Zem Zem notes “gets spongy – wet, the ‘greatcoat’ flaps about my feet”, so it is likely that he had to procure his own. These were advertised in newspapers such as the Tailor and Cutter at a cost of 17/- for a sleeveless leather jerkin lined in army grey and suitable to be “worn over tunic for Officer or Tommy”.

Other newspapers of the time carried many accounts from men in the trenches extolling the virtues of the leather jerkin. To keep up with demand situations vacant adverts for leather machinists regularly appeared in the press, and in one notable case a trade union officer was prosecuted for organising a strike of leather workers in East London. According to the London Daily News of 30th December 1916, “the prosecution was undertaken to stop attempts to prevent workmen from working at necessaries for the war, the necessaries in this instance being soldiers uniforms and leather jerkins”.

Such was the popularity and practicality of the leather jerkin it continued to be issued in WWII, virtually unchanged to the WWI design, with large buttons fastening up the middle, thick wool inside and soft leather protecting the wearer from the elements. The jerkin remained a common sight amongst labourers and manual workers in the decades following the war, and retired officers tending to their gardens. Unfortunately we don’t know whether Zem Zem hung on to his.

By Craig Durham, volunteer at The Highlanders’ Museum (Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection)