Highlanders in Cape Town

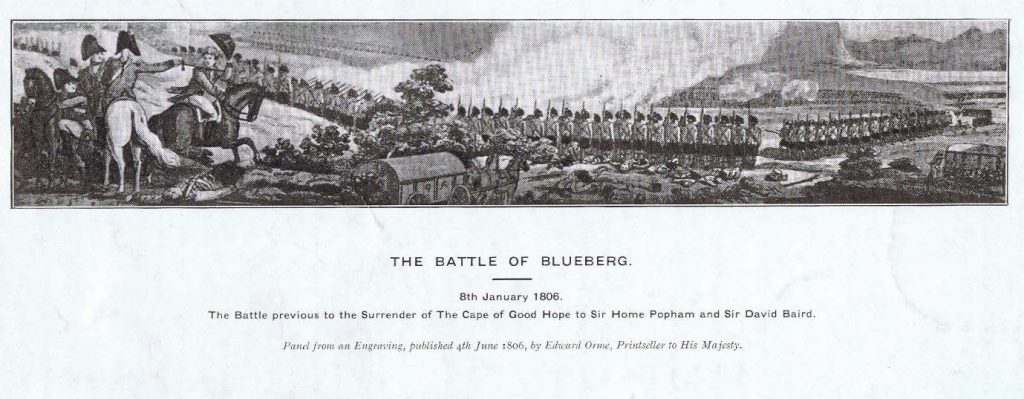

The Battle of Blaauwberg 8th January 1806 – Part 1

On the 4 January 1806, the lookout stationed on Signal Hill above Cape Town, spotted sails appearing over the horizon and immediately sent a message to General Jan Willem Janssens at the castle of the approaching flotilla. The fleet had been expected after two French ships, the Atlanta and the Napoleon, had arrived in the Cape the month before. They had mentioned that they had passed a large fleet of British ships heading south, and Janssens knew he was about to be attacked. Cape Town was about to enter the history books as part of the Napoleonic Wars.

The British fleet was under the command of Captain Sir Home Riggs Popham who had been given nine ships of the line to escort fifty-four transports laden with men and supplies. The task was to take the Cape from the defending Batavian Republic and to ensure that Napoleon’s fleet could not gain a port which would endanger the British commercial route around the Cape of Good Hope. On board the transports were an army under the leadership of General Sir David Baird, a man with previous experience of the defences of the Cape and a man well known for expertise in leading campaigns in the southern oceans. Expecting the Batavians to have a defending force exceeding 5000 men, Baird had insisted that he needed 6000 at least to capture the Cape. Although originally given only 4000, Baird finally managed to combine a force over 6000, including seven regiments of foot, a cavalry of dragoons and a small artillery. The main body of men and supplies assembled in Cork, Ireland before leaving in September 1805. Their journey of three months would take them to Madeira, on to South America before heading across the Atlantic to the Cape.

In the evening of the 4 January, the large fleet anchored in the straits between Robben Island and the African coast. Baird had warned Popham of the deadly hot shot that the forts around Table Bay could fire, and not to enter anywhere near safe anchorages of the bay. At 1:00am on 5 January, Baird gave the order for the first landing party to man the boats. The 59th Regiment and the Dragoons were given the task of setting up a bridgehead at Big Bay, the closest beach to the ships. The men and horses were lowered into the large landing boats then rowed towards the coast in darkness and poor weather conditions. At about 3:00am it was evident that landing at this location was going to be unsafe and the decision was made to turn around and head back to the fleet.

Baird called a meeting of his commanders to discuss an alternative plan should they be unable to land the troops from the anchorage at Robben Island. He ordered Brigadier General Beresford to take the Dragoons and the 38th Regiment north, to land at Saldanha Bay, where he knew there were large farms which could supply additional horses to the Dragoons who required mounts. They would then march south and meet up with Baird who hoped to land the remaining troops closer to Cape Town. In the late afternoon of the 5 January nine of the transports along with HMS L’Espoir sailed north to Saldanha Bay.

On the morning of the 6 January the weather had calmed enough for Baird to be confident of getting his men on shore. Now that that Big Bay was not suitable, the men of the Highland regiments were ordered to make for Losperds Bay, the area now known as Melkbosstrand. The three regiments were loaded on to the large rowing boats and headed for the shore with cannon support from the two gun brigs, HMS Encounter and HMS Protector, anchored close to the beach. The initial landing was not good for the Scottish troops, and one of the first boats hit rocks and capsized; all 36 soldiers, a drummer boy and several the sailors drowned, just a matter of a few hundred feet from land. The following boats had more success and despite a skirmish on the beach, against defending militia in the sand dunes, the British troops soon gained a foothold, establishing a landing place for the invading army to disembark. Over the next 24 hours Baird landed 4500 men on to the beach ready to march on Cape Town.

After getting the message from Signal Hill, General Janssens had a signal-cannon fire from the castle to alert the outlaying residents of the arrival of the fleet. Within hours Burger Militia, as far away as Swellendam, had received the message and were mustering to head to Cape Town and to defend their lands from the invading forces.

Over the next couple of days men arrived in the town to give Janssens a total of 3,122 men of different backgrounds to defend the Cape. On the 7 January, leaving a holding force under the command of Lieutenant Colonel H C von Prophalow, Janssens left the castle and moved his army to Rietvlei with just a meagre contingent of 2061 men of differing nationalities. Under his command were three recognised regiments of men: the 22nd Batavians, the Hottentot Light Infantry and the 5th Battalion Waldeckers – a professional group of soldiers from the German principality of Waldeck. Along with these men were a naval contingent from the two French ships and the 5th Artillery manned by Javanese and Malays under the command of Lieutenant Pellegrini. In addition, Dragoons from Swellendam and Stellenbosch gave Janssens a mobile accessory which could keep an advancing force at bay with accurate shooting by skilled horsemen. From Rietvlei, Janssens took his men up a wagon trail road, and camped the night at Blaauwbergsvallei Outspan. Janssens and his commanders took the opportunity to spy on the British and rode to Ronde Kop, a small hill east of Blaauwberg Hill, above the British encampment. Here Janssens assessed that their best chance of success would be to bring their mobile artillery up on to the high ground the next morning and to keep the British on the beaches. Stopping them from leaving the beach would allow time for reinforcements to arrive from Europe, which had been mentioned by the French captains on their arrival. Unbeknown to either Janssens or the British, Trafalgar had put paid to any French ships coming south.

In the early hours of Wednesday 8th January 1806 both armies left their overnight camps and headed towards each other. Having been alerted by his pickets on the foothill of Blaauwberg, Janssens was soon to see the redcoats of the British emerging in two columns; his plan to gain the heights above the British encampment was now foiled and he had no option but to set up his men in a defensive line. After a quick discussion with his commanders, he set out a line from the sand dunes below Blaauwberg and across the junction of roads that the British were looking to use to advance on the town.

Baird had stolen Janssens’ thunder by mobilizing his men at a very early hour and forming them into two brigades. First Brigade, under the command of his brother Joseph, in the absence of General Beresford, comprised the 24th, 59th and 83rd Regiments of Foot. They were to advance through the saddle between Blaauwberg Hill and Rondekop taking with them the few artillery pieces that Baird could call on. These guns, two howitzers and six field guns, had to be man-hauled by sailors as only the officers had any horses that could be called upon. The Second Brigade was under the command of General Fergusson and comprised the 71st, 72nd and 93rd Regiments of Foot, all being Scottish and therefore were known as the Highland Brigade.

Baird took up a position on Ronde Kop, and in the early morning light saw the Batavian forces lined up on the plain below. Baird was still convinced he was up against a force of 5,000 and only seeing half that number, wondered if there was a reserve hidden behind Kleinberg to his right. He ordered the grenadiers from the 24th to advance with one of the field cannons and scale the northern slopes of Kleinberg to see what was beyond. This manoeuvre was spotted by Janssens, and he ordered his Swellendam Dragoons to ride up the hill to thwart the attack by the 24th. At the top of the hill the first encounter of the battle took place, and the British withdrew with a number of casualties – including Captain Andrew Foster – shot of his horse at close range. Baird ordered the light company of the 71st to assist the 24th and between the two they managed to secure the hilltop

By now it was evident that the First Brigade was getting slowed up by a dune field at the base of Blaauwberg Hill. The Sailors had managed to get the two howitzers through the sandy track and had attained a suitable firing position for them below Baird’s viewpoint. Baird then ordered General Fergusson bring his Highland Brigade off the main wagon track they were marching down and bring them into their ranks. 2,000 Highlanders in 4 rows spread out in the fynbos (thick bush) and prepared to advance on the defensive forces. The artillery pieces were now on a high point behind the advancing Highlanders line so could provide covering fire over the heads of the Scottish troops.

General Janssens rode along the line of the Batavian force spread out across the main wagon track with his Artillery and Dragoons holding the right flank, sand dunes protecting his left and in the centre of the line he was depending on the 5th Waldeck battalion. Shouting words of encouragement, the men cheered Janssens as he rode past, all except the Waldeckers who in the opening salvos from the British guns were beginning to take casualties.

With the howitzers firing over their heads the Highlanders began to advance towards the Batavian line. As they moved through the thick vegetation, they began to become constricted by the sand dune on their right and the defender’s artillery on their left. This caused the three regiments to close and eventually forced them to change from a line to a column. As they moved so they started to also take casualties and at about 100 yards from the enemy General Fergusson decided that the men needed to flex their muscles. The leading regiment was the 93rd, and the front ranks were ordered to load their muskets and fire. The distance was too great to cause any damage, but it boosted morale enough for the men to charge through the smoke-laden air under volleys of Batavian musket balls and incoming cannister shot from the cannons.

Janssen’s orders to his commanders in the morning had been to be prepared for a fire and withdrawal; using alternating artillery and volley fire as they moved back allowing the dragoons to encircle any advancing troops. However, the Waldecker’s commanders had not been party to the instructions from Janssens and became confused when they saw the men either side of them fire and move back. Already demoralised with being targeted by the British cannons and now seeing the Highlanders baring down on them, the Waldeckers started to revolt. No words of encouragement from Janssens could stop the desertion and soon a hole opened in the centre of the line. The Highlanders took advantage of this and as the defenders desperately closed up the Scotsmen piled into them with their bayonets.

A short, bloody, encounter took place with close-up fighting between the Scottish, French and Batavian soldiers. Janssens realised that his men would not be able to withstand the pressure of the fight as well as the additional regiments of the first brigade waiting behind the kilted troops. He ordered the Batavian men to retreat leaving the exhausted Highlanders who were too tired to pursue their foe.

The Battle of Blaauwberg was over costing the lives of 15 British soldiers, over 250 men of other nations on the day, and probably three times as many over the next weeks from wounds inflicted. Janssens retreated up to the Hottentot Holland Mountains, east of Cape Town with a depleted army.

After re-grouping at Rietvlei on the evening of the 8th Baird marched his Army on towards Cape Town where he was met by Lt-Gen H C Von Prophalow, who on the 10th January, signed an agreement of capitulation of the Town. After his long march south from Saldanha Bay, Beresford was given the task of searching for Janssens and on the 17 January the two men met in the Hottentot Holland mountains. The following day Janssens signed the final Treaty of capitulation ending the centuries long hold on the Cape by the Dutch.

This blog was produced for The Highlanders Museum by Dave Honour, a registered Battlefield Tour Guide with Western Cape Tourism.